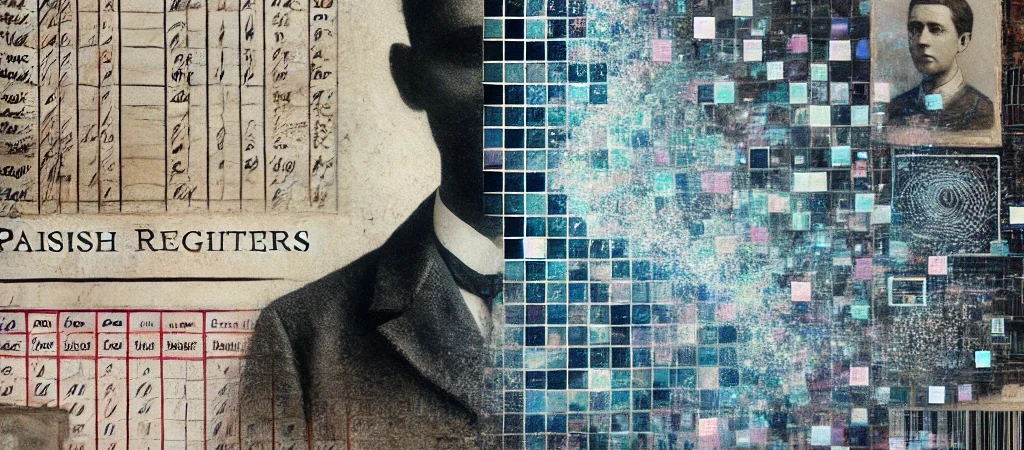

This post is part of Citizen Erased, a series exploring how recordkeeping systems shaped and suppressed identity.

Part 5 – Escape: John Acton Leaves the System followed the first confirmed break from the pattern. This Part 6 – The Church as Asset Manager asks whether clerics acted more like accountants than shepherds.

This is Part 6 in your Citizen Erased blog series. This entry reflects on the uncomfortable implications of institutional surnames, data-driven identity, and the limits of genealogy when lineage is a product of policy — not blood.

Ghosts in the Tree

Why Genealogy Isn’t Always Genetic

We like to believe that a family tree reflects lineage.

Parent to child, generation to generation, branching in blood.

But what if the names you inherit aren’t ancestral?

What if they’re administrative decisions, issued by a system that cared more about throughput than truth?

This is the reality for many lines traced through the workhouses and parishes of 18th-century England — and especially for families like the Actons of Lichfield.

The Illusion of Inheritance

By all appearances, the Lichfield Actons trace back to:

- Humfrey Acton m. Joanne Groves in 1588

- Through William, John, Thomas, and George

- Down to John Acton (1831) who left the Lichfield workhouse for London

But this is likely a narrative reconstruction, not a biological record.

Our own research across:

- Parish registers (FreeREG, 1600–1850)

- GEDCOMs

- Poor Law documents

…suggests the surname Acton was reused across multiple, disconnected pauper children — with no verifiable link beyond geography and policy.

Names Without Blood

The deeper we dug, the clearer the pattern:

- Dozens of “Acton” baptisms appear between 1740–1800, often with no parents listed

- Multiple Acton children are buried within months of baptism

- Repeated name patterns (John, Jane, Thomas, Sarah, Mary) reset every few years

- No continuity of address, trade, or family grouping emerges

Instead, the Acton name appears to function like a template — reused to manage institutional identity.

This is not genealogy. It’s paperwork.

Institutional Genealogy: A Working Definition

Institutional genealogy is the idea that:

A family tree can be constructed by tracking how institutions assign and reuse names to categorize and manage human populations — regardless of blood relation.

It is a tree of:

- Paper trails

- Baptism registers

- Bastardy bonds

- Settlement orders

- Inmate lists

…and it serves bureaucratic function, not personal continuity.

The Tragedy of the Ghost Family

The Lichfield Actons may never have existed as a single family unit.

Instead:

- Each “Acton” child was likely a workhouse birth, or assigned the name upon intake

- Some were later removed to other parishes under Settlement Law

- Others entered apprenticeships or domestic servitude

- Most disappear from records by age 20

Their “tree” is a ghost network of:

- Lives that never intersected

- Names reused for simplicity

- Human identity flattened into ledger entries

Why This Matters for Genealogists

If you descend from a workhouse surname — or your tree “explodes” into a crowd of poor baptisms — you may be tracing administrative identity, not ancestral blood.

Here’s what to watch for:

| Warning Sign | Possible Meaning |

|---|---|

| Many children of same name born close together | Reused template surname |

| No parent names or inconsistent ones | Institutional registration or foster intake |

| No trace into adulthood | Early death, removal, or erased from records |

| Spikes of baptisms without marriage links | Bulk child intake or mass abandonment |

| Surname appears across parishes but lacks continuity | Assigned identity, not family history |

The Limit of the Tree

Genealogy software doesn’t handle this well.

- It assumes one-to-one relationships

- It wants linear descent

- It asks: “Who were your parents?” — not “Who processed your identity?”

But if the Actons were a ledger surname, not a bloodline, then building their tree becomes an act of forensic sociology, not ancestry.

You are no longer asking “Where did I come from?”

You are asking “What system created this identity?”

Historical Context

This wasn’t unique to Lichfield. Across England:

- Workhouse children were assigned surnames like Smith, Clark, Hill, or a local toponym like Acton or Burton

- Parish records reflect the needs of the Church and vestry, not of the child

- Many surnames in modern Britain owe more to administrative function than heritage

Think of it as population accounting.

What to Do If This Is Your Tree

Don’t give up. Change the question.

Instead of:

“Who was the father of John Acton b.1759?”

Ask:

“What was happening in Lichfield in 1759 that produced five boys named Acton?”

Instead of:

“Why can’t I find the marriage of Thomas Acton and Rosamund Walton?”

Ask:

“Was Rosamund a real mother — or a reused placeholder name in the workhouse?”

This doesn’t erase your heritage.

It repositions it as part of a larger, structural story — one that you can now tell.

Sources and References

- Frost, Ginger. Illegitimacy in Britain, 1700–1920

- Snell, K.D.M. Parish and Belonging

- Higginbotham, Peter. The Workhouse in Lichfield

- National Archives: Poor Law and Settlement

- FreeREG Parish Records (Staffordshire: Lichfield, 1600–1850)

Coming Next

Post 7: “The Throughput Machine: Church, Crown, and the Child Ledger”

We’ll step back even further to look at the full system: Church recordkeeping, Crown taxation, local labour demands — and how every pauper child helped keep the wheels turning.