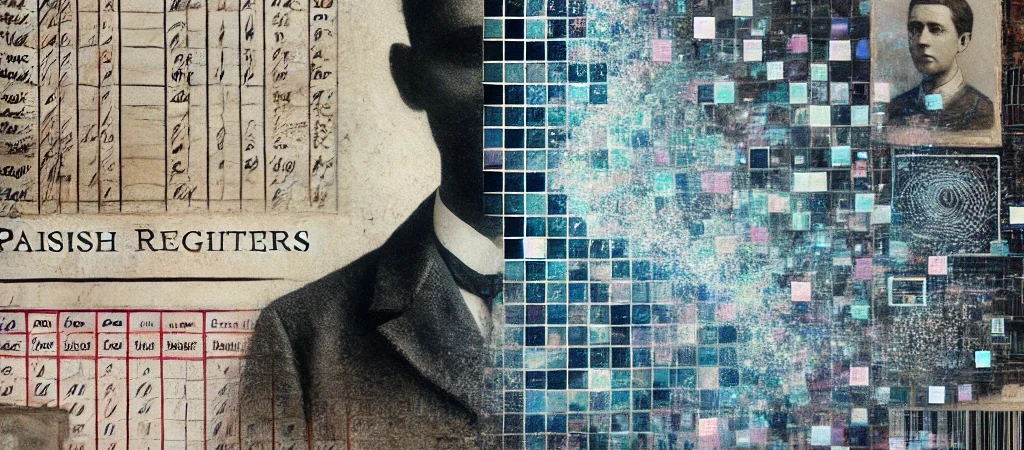

This entry in Citizen Erased profiles the first Acton who may have broken the cycle of institutional identity.

Part 4 – The Economics of the Actons traced the value of naming.

Part 5 – Escape: John Acton Leaves the System follows a real man, born in the workhouse, who migrated to London and forged a verifiable life. This piece follows the journey of pauper children into adulthood, tracing how they were handled by the system once they aged out of usefulness — or, worse, became liabilities.

From Ledger to Lockup

When Pauper Children Grew Up

They started as names in a register. Illegitimate, unwanted, or unrecorded. They were baptised in bulk, buried in batches, and fed through a system that tracked only what it needed to.

But what happened when those children — the “Actons” and others of Lichfield — grew up?

This post explores the final phase of institutional throughput: the adult poor, and how pauper children, once a source of economic justification, became burdens to be managed, relocated, institutionalised, or erased.

Growing Up: The Expiration of Use

By age 12 or 13, a pauper child could no longer be easily placed as an apprentice.

By 16–18, they might be dismissed from the workhouse.

By 21, many simply disappeared.

Why? Because they had aged out of usefulness.

Parishes had three options:

- Send them into service or military

- Assign them to another parish if not “settled”

- Commit them to an asylum or prison

This wasn’t a failure of the system.

It was the system.

Case Study: Lichfield’s Invisible Adults

The FreeREG dataset shows dozens of baptisms for ACTON children in Lichfield between 1740–1790.

But cross-reference these names with:

- Marriage registers

- Apprenticeship indentures

- Burial records after age 25

And they vanish.

Only a handful — such as John Acton (b.1790) and his son John Acton (b.1831) — reappear later in life. Most are gone. Not just from life, but from paper.

This suggests:

- Many died young and unrecorded

- Others were absorbed into military or industrial placements without parish tracking

- Some may have changed names, identities, or were committed to asylums

Settlements and Removals

Under the Settlement Act of 1662, every person belonged to a specific parish. If a pauper adult moved somewhere new — and couldn’t prove a trade, marriage, or long-term tenancy — the local authorities could legally remove them back to their parish of origin.

This meant that:

- Children born in Lichfield workhouse were tagged for life as Lichfield charges

- If they left, they were chased down and removed

- Lichfield kept receiving its own surplus, again and again

The name Acton was not a family.

It was a claim of liability.

Into the Asylum

By the early 1800s, especially after the Lunacy Act of 1845, adults who had once been poor children were increasingly sent to county asylums.

These were not short-term mental health centres. They were:

- Overflow mechanisms for the Poor Law system

- Destinations for adults with cognitive disabilities

- Lockups for the disruptive, vagrant, or infirm

Lichfield’s pauper children had few ways out.

Those who didn’t die in youth, or weren’t absorbed by marriage or war, often ended up here.

Names That Don’t Move

Compare with other surnames in the same parish:

- Smith, Ward, Hill — show typical transitions across birth, marriage, occupation, and death

- Acton — spikes in child baptisms, sudden drop at adulthood

This pattern is administrative, not hereditary.

It’s as if the Actons were programmed into the parish system, never meant to persist beyond usefulness.

Prison and the Vagrant Acts

Adults who were poor and jobless were also criminalised under vagrancy laws:

- Sleeping rough, begging, or having no visible means of support could result in jail

- Women could be arrested for “idle and disorderly conduct” or prostitution — even if that meant only being visibly poor

Thus, the Lichfield Actons:

- May have been institutionalised as children

- Criminalised as adults

- Forgotten as humans

Their identity, carefully assigned for bureaucratic ease, became a cage.

The Acton Loop: A Life in Four Phases

| Phase | Age Range | Institutional Role | Typical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | 0–5 | Pauper child, baptised | Workhouse intake, early burial |

| Childhood | 5–12 | Apprentice or labor | Sent to trade, nurse, or service |

| Adolescence | 13–20 | Surplus youth | Dismissed, migrated, erased |

| Adulthood | 20+ | Liability | Prison, asylum, or re-institutionalised |

Modern Parallel: Data Expiration and Policy Drift

You can see echoes of this today:

- Foster children who age out of care

- Ex-inmates released without support

- Homeless adults criminalised for poverty

The digital version is cleaner — CSV files, system flags, performance targets — but the logic is unchanged:

People are categorised by value, not by humanity.

Sources and References

- Poverty and Poor Law Reform in Nineteenth-Century England, David Englander

- The Workhouse: A Study of Poor Law Buildings in England, Historic England

- Children and the Poor Law, Peter Higginbotham

- National Archives: Settlement and Removal Orders

- FreeREG Lichfield Transcripts (1600–1850)

- British History Online: Lichfield Workhouse and Parish System

What’s Next

Post 6: “Ghosts in the Tree: Why Genealogy Isn’t Always Genetic”

We’ll reflect on the implications for family historians. How do you build a tree when the names are assigned, the lives are undocumented, and the lineage is policy-driven?