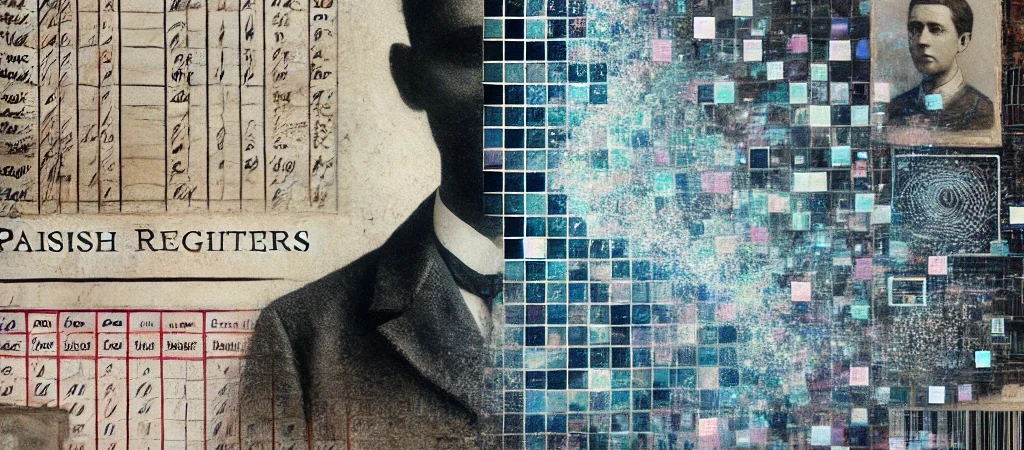

In Citizen Erased, we now confront the central unit of value in the Poor Law system: the child. Part 6 – The Church as Asset Manager mapped the administrators.

Part 7 – The Children Are the Asset explores how infants became entries—livelihoods for parishes, and liabilities if not tracked.

This is Part 7 of our Citizen Erased series. This entry pulls the lens back to uncover the full machine that processed pauper children like the Actons — not as families, but as fuel.

The Throughput Machine

Church, Crown, and the Child Ledger

Beneath every poor law register, every workhouse ledger, and every “Acton” child in Lichfield, there was a system. It spanned Church, State, and industry. It didn’t just manage the poor. It used them.

This post reveals how the institutional treatment of pauper children — from baptism to burial — was not a series of accidents, but the result of a coordinated, hierarchical throughput machine designed to sustain power, generate revenue, and maintain social order.

Children as System Inputs

In prior posts, we examined how poor children were:

- Named administratively

- Tracked through parish registers

- Cycled through workhouses, apprenticeships, asylums

But to grasp the why, we must understand who benefited.

The Engine Room: Church, Crown, and Local Economy

1. The Church: Registry and Morality Broker

- Maintained baptism, marriage, burial registers

- Collected tithes and parish rates

- Framed poverty as moral failing (sin of the parents)

- Reinforced legitimacy through ritual and naming

2. The Crown: Settlement and Control

- Required records to assess tax base and military fit

- Used the Settlement Act (1662) to control internal migration

- Enabled removal orders to keep populations fixed to location

- Oversaw the design of the New Poor Law (1834) to centralize costs and discipline the poor

3. Local Industry: Labour and Disposal

- Took in children as apprentices (wool mills, brickworks, foundries)

- Housed surplus in exchange for parish fees

- Benefited from reduced wages due to over-supply of labor

These were not siloed parts. They were cogs in a well-oiled machine.

The Workflow of Throughput

Let’s break it down like a flowchart.

Phase 1: Entry

- Pauper woman gives birth (in workhouse or parish)

- Child baptized and assigned surname (e.g., Acton)

- Entered into register

Phase 2: Categorization

- Age, health, parentage, and liability assessed

- “Bastardy bonds” pursued or forged

- Child deemed parish responsibility or shunted elsewhere

Phase 3: Processing

- Sent to nurse or foster (0–5)

- Workhouse internment (5–12)

- Apprenticed or placed (10–16)

Phase 4: Output

- Productive: becomes laborer, soldier, servant

- Disruptive: sent to asylum or prison

- Redundant: dies and is buried; entry closed

The Metrics That Mattered

What was counted?

- Baptisms (proof of duty done)

- Burials (liability ended)

- Apprenticeships (success)

- Removals (not our problem anymore)

What wasn’t?

- Happiness

- Health

- Family connection

- Continuity of care

Names like Acton became tokens to measure throughput — not lineages to preserve.

Profiteers of the Machine

| Stakeholder | What They Gained |

|---|---|

| Church Vestries | Budgets, control, moral authority |

| Parish Overseers | Salaries, social standing |

| Landowners | Cheap child labor, rural stability |

| Industry Owners | Low-cost, no-contract workforce |

| Crown (State) | Population data, military stock, taxable heads |

Modern Parallels (Yes, Again)

The machinery is digital now. But the logic remains:

- Welfare systems assign identity and track performance

- Foster care turns children into transferable “cases”

- Education funding tied to registration numbers

If the poor today are managed by dashboards, the poor then were managed by ledgers.

Genealogy as Forensics

This is why researching families like the Lichfield Actons becomes forensic.

We’re not just tracing ancestors — we’re mapping system outputs.

Genealogy becomes investigative journalism.

A Diagram Worth Picturing

Imagine this (and we can generate it for your blog):

[ Church ]

||

[ Unwed Mother ] --||--> [ Baptism Register (Surname: ACTON) ]

|| ↓

[ Vestry Budget Justified ]

↓

[ Workhouse Entry ]

↓

+---------> [ Sent to Nurse / Died ]

| ↓

| [ Survived to 6 ] ---------------------+

| ↓ |

| [ Apprenticed / Removed ] |

| ↓ |

| [ Enters Adulthood ] |

| +--------+--------+--------+ |

| | | | | |

| [ Asylum ] [ Prison ] [ War ] [ Unknown ] <--+

Names like Acton don’t just link people.

They reveal the system that created them.

Sources and References

- Higginbotham, Peter. The Workhouse: Lichfield

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531–1782

- Tomkins, Alannah. Pauper Voices and Lives: Poor Law Memoirs and the Workhouse Experience

- Goose, Nigel. “The Children of the Poor.” Local Population Studies (2001)

- FreeREG: Parish Baptism, Burial and Marriage Records

- National Archives: Poor Law, Vestry and Settlement Papers

Coming Next

Post 8: “The Names That Weren’t Theirs”

We’ll dive deeper into the use of surnames like Acton as administrative scaffolds — reused, assigned, and recycled by clerks, not kin.