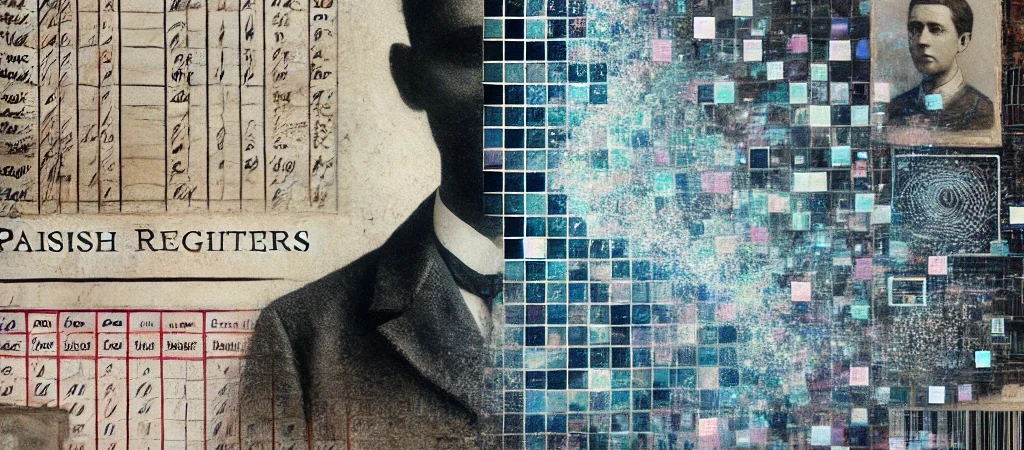

In Part 3 – Assigned Identity, we explored how names could be administratively manufactured. This Part 4 – The Economics of the Actons investigates why this naming occurred—whether children were tied to financial value in the relief system.

This post synthesizes what we’ve learned about the Actons and explores the systemic use of children as institutional commodities within the poor relief system.

Surplus by Design

How the Poor Became England’s Most Useful Resource

If it feels like the 18th-century Actons of Lichfield appeared out of nowhere — multiplying across baptisms, disappearing into burials, and repeating through generations — that’s because they did. But not as a biological family. As a managed surplus.

This wasn’t chaos. It was design.

The population boom of the 1600s and 1700s was not just an accident of improved food supply or the post-plague recovery. It became an opportunity for Church, State, and Industry to create a throughput of human resources: poor children born into dependence, processed through the parish system, and reallocated as economic fuel.

This post unpacks how that surplus was manufactured, managed, and monetized.

Children: An Unspoken Asset

In a world of agricultural transition, enclosure, and urbanization, landowners no longer needed surplus adults. But children were another matter.

They could:

- Work cheaply in fields, mills, and houses

- Be apprenticed under long contracts

- Occupy institutional beds at lower cost

- Serve as justification for local parish budgets

And crucially: they couldn’t say no.

The state didn’t need to force fertility. It simply needed to capture the output of the poor, and turn their offspring into a regulated stream of bodies.

The Lichfield Actons as Evidence

The FreeREG dataset from Lichfield (1600–1800) contains over 200 entries for ACTON and variants — far more than expected for a single family. And what do we find?

- Children baptised under Acton without listed parents

- Burials of infant Actons in bulk, many within days of baptism

- Repeat baptisms of the same names (Jane, John, Thomas, Mary)

- Multiple marriages with no links to earlier entries

When examined through the lens of genealogy, this is frustrating.

When examined through the lens of institutional asset management, it begins to make sense.

A System Designed for Throughput

The 18th-century Poor Law parish functioned like an early ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) system:

- Input: Pregnant women, often unwed or widowed

- Process: Birth recorded, baptism performed, surname assigned

- Storage: Child placed in workhouse, almshouse, or informal care

- Output: Child sent to labor, married off, apprenticed, or buried

Surplus was not a problem.

Surplus was the point.

Every extra birth meant:

- More ratepayer support collected

- More justification for poor relief expansion

- More indentures signed with local businesses

- More dependent bodies feeding the system

The Feedback Loop of Pauper Breeding

There is no kind way to phrase this: poor women were not encouraged to have fewer children.

They were expected to produce more.

Why?

- Illegitimacy fines were profitable

- Bastardy bonds extracted maintenance from named (or fictional) fathers

- Every child increased the justification for vestry salaries and workhouse expansion

- Foundries, farms, and factories demanded fresh labor

And once born, these children had few exits.

If one survived to adulthood, they might become a laborer — or return as a pauper, repeating the cycle.

Institutional Bed Management

Workhouse records from Lichfield (where surviving) show that adult beds were limited, but child space was often reused:

- Infants entered at birth

- Reassigned to nurse or removed at age 3–7

- Replaced immediately by the next

- Little record of where they went, especially girls

Some children vanish from all registers — likely sent into informal domestic placements or buried anonymously.

From a parish perspective, this wasn’t negligence. It was efficiency.

The Church and the Ledger

Parish churches kept the registers, but they also ran the system:

- Baptisms = legitimacy

- Marriages = legality

- Burials = clearance of liability

The same rector might baptise a pauper infant, sign off on their apprenticeship at 9, and bury them at 17.

All with full institutional blessing.

Meanwhile, the name Acton carried through, not because of heritage — but because it was on file.

A safe, local, reusable surname that made recordkeeping clean.

The Economics of Children

| Function | Role of Child | Institutional Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Baptism | Entry into Church/paper | Registers kept updated, proof of action |

| Workhouse entry | Institutionalised care | Poor Law budget justification |

| Apprenticeship | Labor asset | Placement fees collected, contracts signed |

| Death/Burial | Record closed | Bed freed, data cleared |

| Reused surname (e.g., Acton) | Tracking token | Easier continuity, fewer clerical issues |

Children were a form of biopolitical currency — not metaphorically, but operationally. Their bodies generated economic and institutional movement.

Modern Parallels (A Taste)

This is not just history.

Modern systems of population management — from foster care to social credit — still manage human life through data.

What changed?

- Digitization replaced parish registers

- Welfare replaced Poor Law

- Metrics replaced morality

But the logic remains: document, manage, assign, output.

References

- Higginbotham, Peter. Workhouses.org.uk – Lichfield Union

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law 1531–1782

- Goose, Nigel. “The Children of the Poor.” Local Population Studies, 2001

- FreeREG Transcripts: Lichfield Parishes, 1600–1800

- Frost, Ginger. Illegitimacy in Britain 1700–1920

- National Archives: Poor Law Union Records

What’s Next

Post 5: “From Ledger to Lockup: When Paupers Grew Up”

We’ll explore what happened to those children as adults — particularly the transition from poorhouse to asylum, military, prison, or anonymity. And how, once grown, they became liabilities instead of assets.