This post is part of Citizen Erased, a 10-part series exploring how historical recordkeeping systems shaped, obscured, and exploited human identity in England.

The previous post, Part 9 – Asset, Not Individual: The Child as Economic Unit, examined how children became the linchpin of workhouse and church economies.

Part 10 – Reclaiming the Narrative looks forward, asking how we might wrest back control over our names, stories, and genealogies.

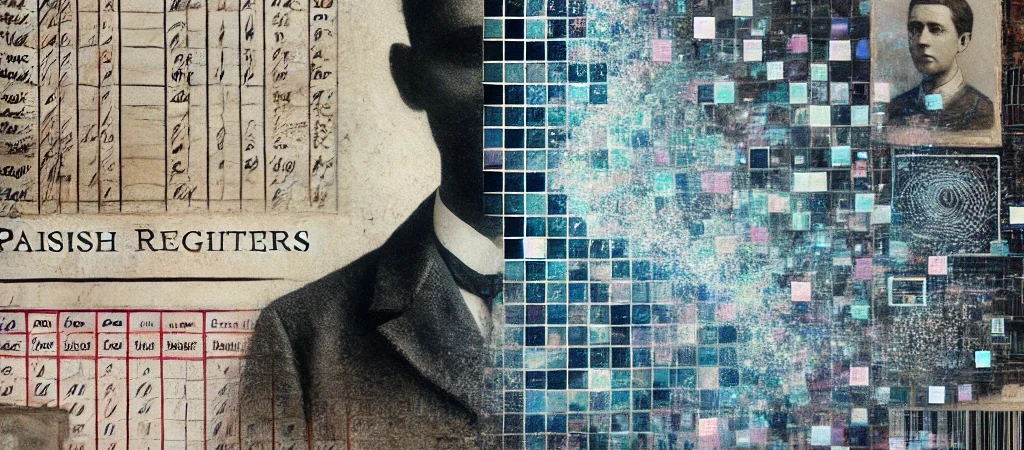

Breaking the Silence of the Registers

Parish registers may seem like dusty relics, but they encoded power. Every baptismal record, burial note, or marriage line was a bureaucratic decision — not always a reflection of lived truth. From 16th century Poor Law accounting to 19th century institutional management, these entries were about control: labor, names, status, property, and bodies.

As we’ve explored in the previous posts, identity was often assigned, not described. Illegitimate children might be inserted into the lineage of a surname with no blood connection. Workhouse-born infants bore inherited surnames of utility, not ancestry.

This series has shown how “Acton” in Lichfield may have been one such administrative name — a kind of surname-as-cipher for throughput in a closed-loop of pauper management.

The Cost of Inherited Identity

When we inherit a family name, we’re not just inheriting lineage. We’re inheriting:

- The state’s choice of how our ancestors were labelled

- The recordkeeping decisions of parish clerks and Poor Law guardians

- The institutional need to categorize and control populations

And as we saw in earlier posts, this could result in:

- Obfuscated family trees, impossible to trace through traditional biological lineage

- Misleading narratives built on paper identities rather than real lives

- Loss of agency in personal and familial memory

Reclaiming: Genealogy as Resistance

So what can be done?

Reclaiming the narrative is not about correcting every missing parent. It’s about taking back the interpretive power from those who assigned names, dictated status, and wrote history on behalf of others.

Here’s how:

1. Reinterpret the data critically

Use parish records not just to build trees — but to question their construction. Ask:

- Who had the power to write this down?

- What incentives did they have?

- Whose voice is missing?

2. Document and publish alternative genealogies

Genealogy blogs, open-source trees, and historical essays give space for interpretations that challenge “official” narratives. You’ve seen it here — even the Actons of Lichfield can be re-understood.

3. Use modern tools, mindfully

DNA testing, AI analysis, and digital archives offer new ways to piece together identity. But they must be approached with the same scrutiny. Data without context can repeat the errors of the past.

A Call to Future Family Historians

If this series has done anything, I hope it’s this:

- Made you rethink what a surname is

- Questioned the neutrality of recordkeeping

- Encouraged skepticism of seemingly objective documents

- Inspired the idea that reclaiming identity is a living project, not a static tree

You are not merely the sum of your parish entries.

You are what you choose to remember, to question, and to retell.

What Comes Next?

This may be the final chapter in Citizen Erased — but not the end of the investigation.

I’ll be working on:

- Visual family reconstructions of the Lichfield Actons

- Annotated GEDCOM timelines highlighting institutional involvement

- An ebook version of this series with expanded footnotes and diagrams

- Possibly… a podcast, for those who’d rather listen than scroll

🕊️ Let’s end where we began — with a question:

Is your family tree a legacy… or a ledger?