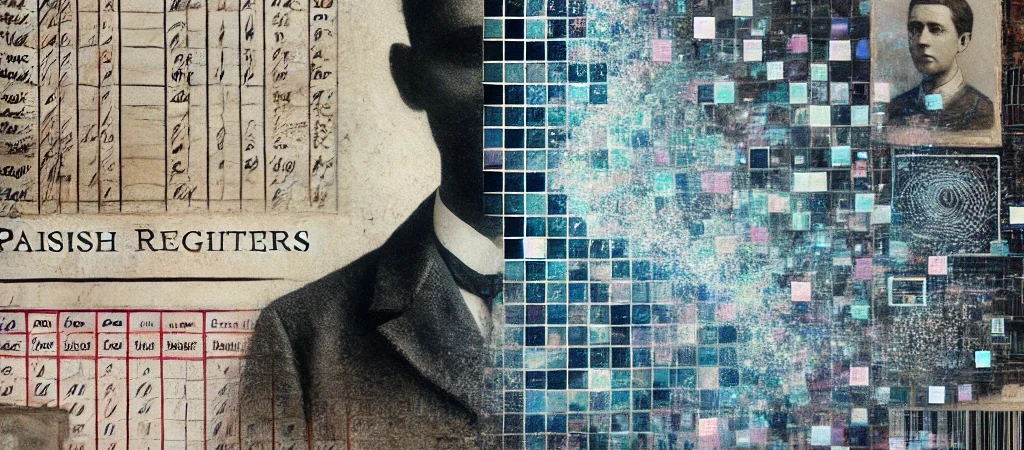

In 18th-century Lichfield, the parish registers are filled with children named Acton. Some were born to women named Mary or Sarah — others to mothers who appear once, then vanish. Most of the fathers are missing. The children themselves rarely reappear in later records. No marriages. No deaths. No land. Just baptisms. So who were they? A sprawling family? Or something else entirely?

Parish Records: England’s First Population Database

Before civil registration began in 1837, the Church of England parish registers were the primary record of life for most people in England. Every baptism, marriage, and burial — particularly among the poor — was documented here. In cities like Lichfield, with strong ecclesiastical control and an operational workhouse, the church was more than just spiritual authority. It was the social registrar.

Under the Elizabethan Poor Laws of 1597 and 1601, each parish was legally responsible for the poor within its boundaries. This included unwed mothers and their children. As such, the church had a vested interest in naming, recording, and tracking these individuals — not always for inheritance, but for liability management.

Reference:

• Hindle, Steve. On the Parish? The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c.1550–1750. Oxford University Press, 2004.

• Snell, K.D.M. Parish and Belonging: Community, Identity and Welfare in England and Wales, 1700–1950. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

The Acton Anomaly: Too Many Children, Too Little Lineage

The Lichfield parish registers from the 1700s to the early 1800s show dozens of children with the surname Acton — more than would be expected from a single family line. Many of these entries list:

- A mother’s name only

- No father present

- The term “base born” or “illegitimate”

- No follow-up in later marriage or burial records

In several cases, baptisms are spaced by only months or a year, to different women with the same surname. No clear household, estate, or family tree connects them.

Example extracted from Lichfield St. Mary’s baptismal register (FreeREG):

- 3 March 1787: Thomas Acton, baseborn son of Mary Acton

- 6 May 1788: Sarah Acton, baseborn daughter of Anne Acton

- 14 January 1790: William Acton, baseborn son of Elizabeth Acton

None of these mothers reappear in parish marriages. The children don’t reappear in burial or probate records. In genealogical terms, they are administrative ghosts.

Bastardy Bonds and the Business of Naming

When a woman gave birth out of wedlock, she was compelled by the Overseers of the Poor to name a father. If one was identified — correctly or under pressure — he was bound by a bastardy bond to pay for the child’s upkeep. If no father could be found or forced, the child became a charge on the parish, and that meant paperwork.

In the absence of paternal identity, children were often:

- Given their mother’s surname

- Or assigned a common local surname already circulating in poor law documentation

In Lichfield, “Acton” may have become just such a surname.

Reference:

• Goose, Nigel. The English Bastardy Order: Contexts and Consequences. Continuum, 2006.

• Staffordshire Quarter Sessions Rolls (via Staffordshire Record Office, ref Q/SB)

Naming as a Throughput System

This pattern suggests that the name “Acton” in Lichfield wasn’t always inherited — it was assigned. Much like issuing a social ID number today, the parish used familiar, respectable surnames to identify individuals whose parentage or social status was ambiguous.

It’s a repeatable process:

- A poor or unmarried woman gives birth

- The child is baptized, with or without her surname

- If she has no stable household or dies shortly after, the child is moved to a workhouse, fostered, or apprenticed

- Their identity persists on paper, but they are no longer traceable as individuals

This is why so many Acton children disappear from the records after their baptism.

Other Floating Surnames in Lichfield

“Acton” isn’t alone in this phenomenon. Other surnames found repeatedly in base-born baptisms include:

- Smith

- Walker

- Webb

- Griffin

- Wilkes

But unlike Smith or Walker, which are occupational and extremely common, “Acton” stands out as:

- Locally significant (possibly borrowing prestige from families in Acton Scott or Aldenham)

- Not overly common in the rest of Staffordshire

- Used repeatedly without continuity

Bloodline or Brand?

This raises serious implications for genealogists. If you are tracing Actons in Lichfield from the 1700s or early 1800s, you may be working with:

- A social label, not a family

- A parish administrative construct, not a biological line

- A surname assigned not by a father, but by a scribe with a mandate to fill a book and close a case

Final Thoughts

“Genealogy isn’t just about who you came from — it’s about who was allowed to exist on paper. The Actons of Lichfield may not have been a family at all. They may have been proof that in old England, your name wasn’t always your heritage — it was sometimes your paperwork.”

Sources Consulted:

- Staffordshire Parish Register Society, Lichfield Transcripts

- FreeREG UK Baptism Index

- National Archives, Bastardy Bonds and Poor Law Papers

- Harleian Society, Visitations of Shropshire (1623)

- Steve Hindle, On the Parish?

- Goose & Newton, Illegitimacy in Britain, 1700–1920