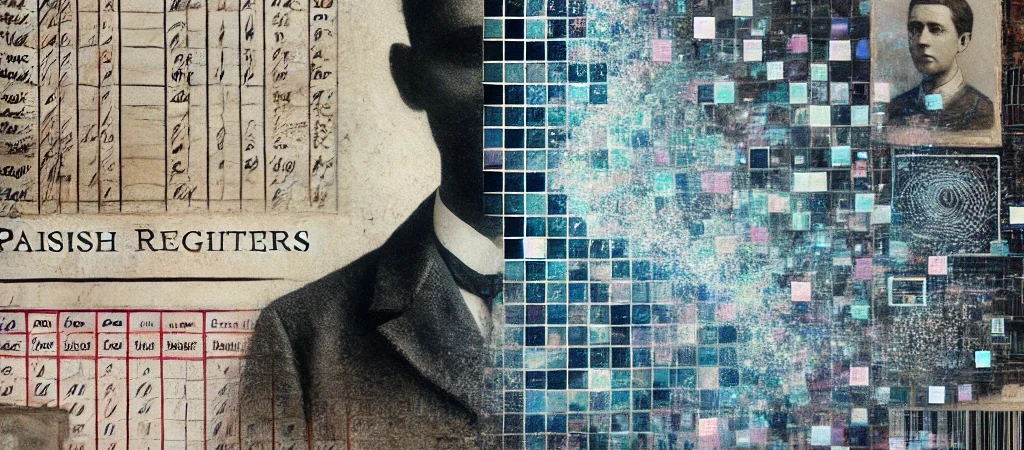

While documenting an ordinary family tree of renters, laborers, and forgotten ancestors, a pattern emerged: lives only recorded when the state or church needed them. This series follows that thread from parish registers to digital ID systems, revealing a continuity of population management—and asking what freedom looks like today.

The Illusion of Progress

The first time a family member appears in the historical record, it’s not in a story. It’s in a ledger.

A baptismal entry: a name, a date, a location.

Later, a census: occupation listed as “carman,” living in a house with three other families.

Eventually, a burial: age, district, cause of death.

No narrative. No context. Just institutional artefacts of their compliance.

Centuries later, their descendants are registered at birth, tracked by smartphone, and issued digital health credentials. They appear not just at milestones—but at every moment.

This isn’t evolution. It’s expansion.

The system that once remembered you three times in your life now records you three times a minute.

This is the timeline of control.

1538 – The First National Recordkeeping Mandate

Henry VIII, seeking to consolidate authority after the break with Rome, mandates that every English parish keep baptism, marriage, and burial registers.

This wasn’t religious nostalgia—it was:

- Population surveillance

- Taxation basis

- Inheritance protection

- Moral regulation

If your ancestor wasn’t in the book, they didn’t exist legally.

For one branch of the family tree, this first appearance came in a small village church outside London. The name was spelled differently each generation, and the ink faded. But it was a record not of life—but of entry into the system.

1837 – Civil Registration: The State Takes Over

Church control weakened, so the state stepped in. Now all births, deaths, and marriages had to be recorded in civil registries.

The goals were:

- More accurate population counts

- Legal validation for property and kinship

- Administrative expansion of the modern state

For working-class families, this meant their children, now born in rented rooms above shops or in tenements, were logged in public ledgers. Their weddings were state affairs. Their deaths cleared with certificates.

Even though these ancestors rarely owned property, their existence had to be acknowledged—for order, not autonomy.

1841–1911 – The Census Era Begins

The national census became a powerful surveillance tool:

- Name, age, address, occupation, household structure

- Conducted every ten years

- Used to direct infrastructure, policy, and labor planning

The family tree shows individuals at different addresses almost every decade:

- From a back room in Fulham to a row house in Acton

- From coachman to gasworks laborer to domestic servant

Each entry reads like a receipt—proof that someone was present, productive, and taxable.

They weren’t tracked for their benefit. They were managed by enumeration.

1900s – Expansion of Institutional Files

As the 20th century unfolded, more institutions began collecting data:

- Military service records (including conscription rolls)

- School attendance logs

- Workhouse and poor law files

- Hospital and asylum registries

If you were poor, sick, uneducated, or disruptive—you were recorded. Not to help you, but to monitor you.

One great-grandparent in the tree, illiterate and underemployed, appears only in a census and then in a death certificate—after being institutionalised. No photos. No stories. Just entries in files.

This wasn’t erasure. It was containment through quiet recordkeeping.

1940s–1970s – The Welfare State and Identity Numbering

Post-WWII, the social contract expanded—but so did the data systems:

- National insurance numbers

- Healthcare IDs

- State schooling records

- Social housing registries

While this era allowed a branch of the family to buy a house, access free education, and retire with a pension, it also required them to become legible to the state in new ways.

Their identity, movements, and entitlements became digital entries—first on punch cards, then on mainframes.

The system gave—and tracked.

1990s–2000s – Digitisation and Mass Surveillance

With the rise of the internet and personal computing:

- Public records moved online

- Corporate data collection exploded

- The state began outsourcing identity verification to private entities

The family’s newer generations—children and grandchildren—entered a world where they were:

- Logged at school via fingerprint scans

- Monitored at work via swipe cards and keystroke logs

- Located by mobile phones and IP addresses

This was no longer recordkeeping. It was streaming compliance.

And nobody asked for permission.

2010s–2020s – Biometrics, Blockchain, and Behavioural ID

Now we reach the current horizon:

- Digital identity wallets

- Vaccine passports

- Carbon credit scores

- AI-generated risk profiles

- Central bank digital currency trials

These systems are justified by efficiency, health, sustainability, and security. But their function is familiar:

- To record

- To control

- To gate access

One ancestor needed a parish signature to marry.

Today’s child needs a biometric ID to attend school and access healthcare.

The interface is smoother. The tracking is deeper. The logic is the same.

A Visual Timeline of Control

| Year | System | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1538 | Parish Registers | Baptism, burial, marriage tracking |

| 1837 | Civil Registration | Legal identity, inheritance, tax |

| 1841–1911 | National Censuses | Labor, infrastructure, planning |

| 1900s | Poor Law / Institutional | Welfare control, social sorting |

| 1940s–70s | National Insurance Numbers | Benefits, employment, taxation |

| 1990s | Digitised Records & IDs | Online access, surveillance economy |

| 2020s | Digital IDs, CBDCs, ESG | Real-time control, access gating |

Each step deeper. Each step smoother. Each step more total.

The Archive Is Now the Interface

For previous generations, recordkeeping happened around life.

Today, it happens within it.

- You can’t work without a digital ID

- You can’t pay without a score

- You can’t move without being geolocated

Your family tree used to be built by inference and fragments. Today’s is being built live, by machines.

What was once a book on a shelf is now a feed on a server.

And the story it tells is not of freedom—but of formatting.

The path from the parish to the platform is clear. We didn’t evolve past serfdom. We refined it.

Once, your ancestors were counted for census.

Now, you’re counted by sensors.

Once, they needed paper to prove existence.

Now, you need permission to transact, move, and speak.

The control has scaled. The system has grown.

But the names in the tree remind us: this logic is old. It simply wears new masks.

From parchment to platform, from ink to algorithm, from faith to biometric—this is the timeline of control.