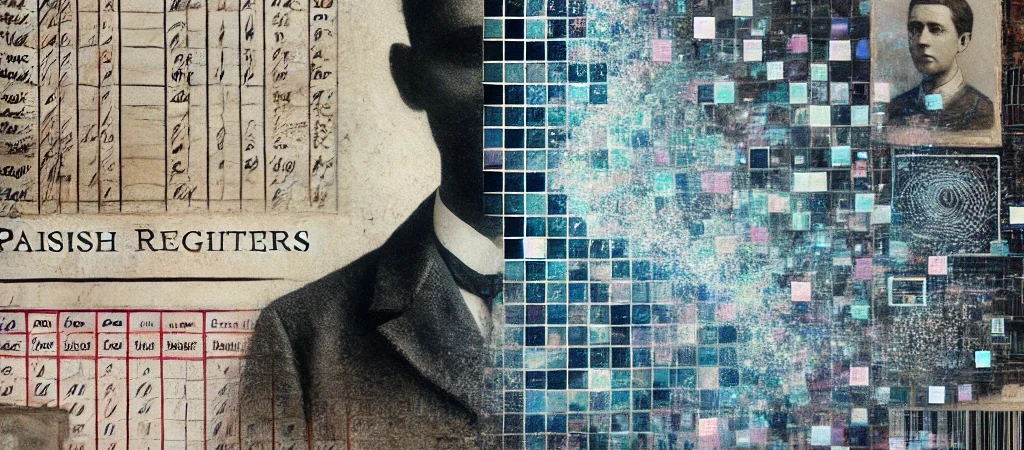

Citizen Erased redefines family history when surnames were assigned for order, not legacy.

Part 7 – The Children Are the Asset revealed the economics of childhood.

Part 8 – Genealogy Beyond Bloodlines reframes ancestry itself, asking what happens when names don’t come from blood—but from bureaucracy.

This is Part 8 of your Citizen Erased blog series. This installment unpacks the final, symbolic consequence of institutional throughput: the reuse and reassignment of surnames like Acton, revealing them not as family names, but as bureaucratic scaffolding.

The Names That Weren’t Theirs

How Workhouses Recycled Identity

What if your last name wasn’t your inheritance — but your paperwork?

As we reach deeper into the archives of Lichfield, and broader Poor Law England, a chilling pattern emerges: names like Acton, once thought to mark lineage, appear instead as tokens of administration.

They weren’t passed down through blood.

They were assigned.

Recycled.

Reused.

This post explores how the surnames of pauper children were not family labels, but institutional tools.

And what that means for genealogy, legacy, and identity.

The Reappearance of Acton

In your FreeREG dataset, the surname Acton appears with unusual frequency in Lichfield between 1700 and 1800:

- Ann Acton, buried 1790

- Rosamund Acton, baptised 1775

- Thomas Acton, baptised 1760

- Elizabeth Acton, baptised 1703

- James Acton, baptised 1733

Many of these records:

- Show no consistent parents

- Repeat first names across short time spans

- Appear in the same parishes and churches (St Chad, St Mary)

This isn’t a tree.

It’s a loop.

Why Assign Surnames at All?

Institutions needed to:

- Record baptisms and burials

- Assign accountability to a parish

- Track settlements for removal orders

- Justify budgets and Poor Rate expenditure

To do that, every child needed a name.

But without a father? Or a mother unable to claim them?

The clerk assigned one.

Surnames used for assignment often followed patterns:

- Toponyms (Acton, Hill, Stafford)

- Common trade names (Smith, Taylor)

- Phonetic variants to obscure duplications (Aston, Astin, Austin)

This is why you find:

- Multiple children named Acton with no relation

- Baptisms clustered around workhouse events

- Duplicated names (John, Mary, Jane) reset each decade

How We Know They Weren’t “Families”

Let’s run through the red flags found in your Lichfield dataset:

| Clue | Implication |

|---|---|

| Multiple baptisms for “Acton” without parents listed | Institutional intake or abandonment |

| Same first names recycled every 5–10 years | New children assigned names from a preset list |

| Burials shortly after baptisms | High infant mortality inside workhouse system |

| Lack of marriage records for “parents” | Names don’t represent couples |

| No continuity in land, occupation, or address | Not a coherent household or lineage |

The conclusion? The Acton surname functioned as a label, not a heritage.

Surnames as Scaffolding

These assigned surnames were used to:

- Facilitate bookkeeping

- Meet legal requirements for baptismal registration

- Place children into settlement jurisdictions

- Populate vestry books and burial ledgers

It made a child recordable.

But it didn’t make them part of a family.

Like scaffolding on a building, it supported the system’s structure — but wasn’t meant to remain.

A Clerical Convenience

Your data suggests Acton, Aston, and similar variants were often used interchangeably. This likely reflects:

- Phonetic spelling by illiterate or semi-literate clerks

- Intentional ambiguity to obscure origin

- Clerical laziness — reusing last week’s name for this week’s child

In some cases, siblings may have different surnames, depending on which clerk recorded them.

This obliterates the traditional structure of a tree.

What This Means for Family Historians

Genealogists face a critical decision:

- Trace the name through assumed bloodline

Or - Interrogate the name as an artifact of social control

For those tracing names like Acton in Lichfield, the question isn’t “Who were my ancestors?”

It’s “Who assigned this name, and why?”

And that’s a very different investigation.

Stories Within the Names

Consider:

- Jane Acton (baptised 1774) appears twice: once in St Chad, once in Cathedral registers. Same name. Different locations. No parents.

- Rosamund Acton appears, vanishes, reappears as burial — potentially unrelated to the previous entry.

Could multiple Jane Actons have existed simultaneously? Absolutely.

Were they sisters? Probably not.

Were they kin? Possibly not.

Were they assigned that name? Almost certainly.

Modern Analogue: Systemic Labeling

This isn’t just a historic problem.

- Foster children today may receive new surnames or adoptive identifiers

- Immigration detention centres assign case codes, not names

- Homeless outreach databases often struggle with repeated “John Does”

The name is what the system needs.

Not what the person owns.

What to Do With an Assigned Tree

You can still build a meaningful family history — but it will look different:

- Trace institutional connections, not bloodlines

- Map workhouse entries, removals, asylums, and indenture records

- Build a social biography of your surname’s usage

Think of it as ethnographic genealogy — a story of how identity was shaped, not inherited.

Sources and References

- Hey, David. Family Names and Family History

- Higginbotham, Peter. Lichfield Workhouse

- McClure, Ruth. Coram’s Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531–1782

- FreeREG: Parish Registers (Staffordshire, Lichfield)

Coming Next

Post 9: “Citizen Erased”

We’ll explore how this research changes our understanding of freedom, citizenship, and belonging — and what happens when people are recorded only to be forgotten.