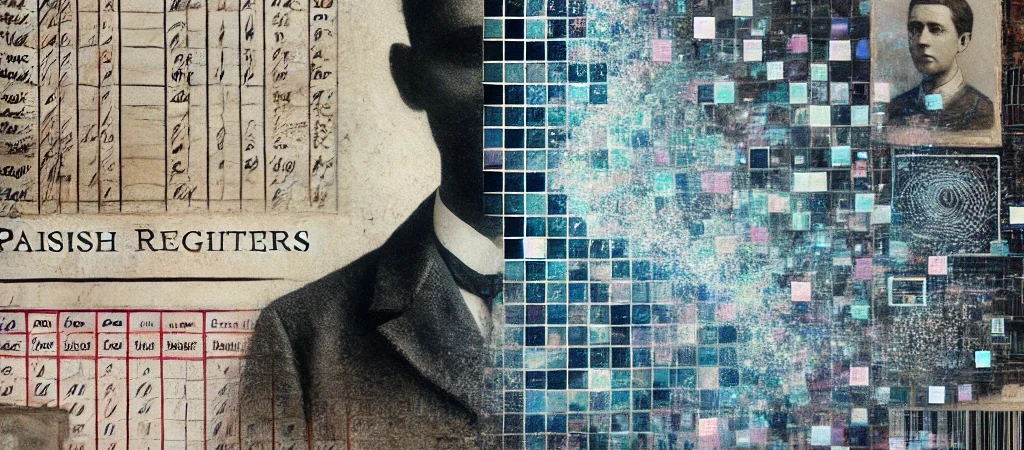

While documenting an ordinary family tree of renters, laborers, and forgotten ancestors, a pattern emerged: lives only recorded when the state or church needed them. This series follows that thread from parish registers to digital ID systems, revealing a continuity of population management—and asking what freedom looks like today.

The Archive as a System, Not a Memory

When I first traced the outlines of a working-class family tree, I thought I was searching for identity. But what I found was a system. Names that appeared and vanished with mechanical precision—baptism, census, burial—nothing in between.

There were no journals, no letters, no stories passed down in ink. Only administrative marks: someone was born, taxed, moved, or died. My ancestors were not remembered. They were recorded.

And those records weren’t made for them—or for me. They were made for the institutions that managed them. From parish scribes to biometric scanners, recordkeeping has always had a function: not memory, but population control.

The Church: Where Institutional Recordkeeping Begins

In 1538, Henry VIII’s England mandated that all parishes begin keeping registers of baptisms, marriages, and burials. This wasn’t a sentimental act—it was a way to:

- Ensure people were baptized into the correct (state-aligned) church

- Monitor fertility and kinship networks

- Track deaths for tithe and inheritance reasons

Early church records were often inconsistent, and only gradually systematized. But they were clear in their purpose: to map the flock, not preserve their individuality.

A name in the parish register meant a person had been brought into the fold, was subject to church law, and would be buried with religious rites—so long as their conduct remained within bounds.

The church recorded the soul for spiritual legitimacy and fiscal visibility.

Civil Recordkeeping: When the State Takes Over

By the 19th century, church authority declined and the state took over. Civil registration began in England and Wales in 1837. The motives were unmistakable:

- Clarify inheritance rights

- Provide accurate population data for planning

- Establish proof of age for school, work, marriage, and military service

Every birth, marriage, and death became part of the state’s filing system. But unless a person transacted with the system again—through crime, poverty, taxation, or property—they disappeared between those events.

The population was now being measured like a resource pool—a record of throughput for labor, policy, and empire. The individual wasn’t the subject. The population was.

The Census: Counting People, Not Knowing Them

Beginning in 1801 and refining by 1841, the British census evolved into a powerful apparatus. While it captured households, occupations, and basic demographics, it didn’t preserve memory. It built a data structure for:

- Taxation and conscription planning

- Urban and military infrastructure

- Labor force analysis and imperial logistics

The census wasn’t about remembering your great-grandfather. It was about planning whether a new railway should be built, or how many young men might be conscripted into the Crimean War.

It’s no accident that most people in working-class lineages appear regularly every 10 years—and yet we know almost nothing about them. Because their names were not being captured for storytelling. They were being captured for governance.

Special Registers: The Poor, the Criminal, and the Disposable

Other state records emerged to manage those who became costly or problematic:

- Poor law applications

- Workhouse registries

- Criminal dockets and transportation orders

- Army muster rolls and desertion logs

These records weren’t exceptions—they were the core infrastructure of surveillance and cost control.

Your name was likely to appear if:

- You required state support

- You broke a law

- You were a young, male body needed for empire

The record was a checkpoint. A justification. A control mechanism.

No working-class ancestor left a paper trail out of pride. They left one because the state needed to contain, conscript, or cost-account for them.

From Paper to Database: The Logic Never Changed

Even as the medium shifted—from scribes to clerks to servers—the logic of recordkeeping remained the same.

The goal was never to know people. It was to structure the relationship between population and authority:

- Who can enter the workforce?

- Who needs aid?

- Who is where?

- Who owes what?

A birth certificate is not a celebration. It’s a ticket to entry—to school, to tax, to healthcare, to legal existence.

A death certificate isn’t closure. It’s clearance—a ledger entry closed, a liability removed.

Even marriage registration was less about romance and more about property, legitimacy, and state-sanctioned union.

The Digital Shift: Total Population Asset Management

Today, the shift to digital recordkeeping has made the system instantaneous, persistent, and global:

- Digital birth registration creates lifelong identity numbers

- Medical records are centralized across jurisdictions

- Location data is streamed through phones and apps

- Facial recognition connects movement to credit scores, passports, and legal permissions

And now, initiatives like digital ID frameworks, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), and health passports aim to make identity fully integrated with access.

No record = no access.

Bad record = restricted access.

Compliant record = conditional participation.

It’s the same control logic, now scaled and automated.

Who Keeps the Records—and Why?

Throughout history, the question has never been “who are you?” but “what are you for?”

And the answer, preserved in ledgers and databases, has always served institutions:

- The state—for taxation, surveillance, and military power

- The church—for conformity and moral control

- Capital—for labor supply, housing, and compliance metrics

Today’s recordkeeping doesn’t just log your existence. It predicts your behavior. It scores your choices. And it connects that score to permission.

Modern Tools, Same Objectives

Whether it’s:

- Carbon footprints

- Vaccine passports

- Credit access

- Border control

- Employment verification

Every tool of modern identity is built on the same foundation: are you legible to the system, and are you behaving as expected?

Genealogy reveals this structure not through story, but through silence. The further back you go, the clearer it becomes that your ancestors were only visible when required—and otherwise erased by design.

What we call ancestry is actually a ledger. A series of moments when someone passed through the gears of a system. Baptized. Counted. Married. Buried.

Their lives were not recorded. Their interactions with institutions were.

That was enough for the state. That was all it needed.

And now, as new layers of recordkeeping emerge—biometric, behavioral, and financial—we return to that same architecture. But this time, it’s constant, digital, and predictive.

We were counted. Now, we are calculated.

The archive has always been a mirror of power. It’s not a family story. It’s a system of control.